This

link leads to a piece of music (in mp3 format,

I made in collaboration with James Hamilton) dedicated to my Burgundian

ancestors. For me it evokes the forceful, warlike advance of the migrating

tribes through the ages.

- Sylvie Bourgouin |

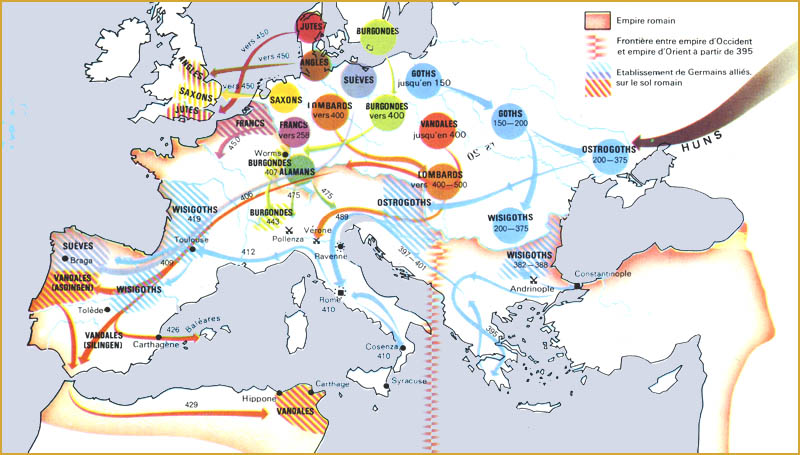

The history of the BurgundiansThe Burgundians or Burgundes were an East Germanic tribe which may have emigrated from Scandinavia to the island of Bornholm, whose old form in Old Norse (The extinct Germanic language of medieval Scandinavia and Iceland from about to 700 to 1350) was Burgundarholmr (the Island of the Burgundians), and from here to mainland Europe. In the Thorstein saga Víkingssonar, Veseti settled in an island or holm, which was called Borgund's holm. (King of Wessex; defeated the Danes and encouraged writing in English (849-899)) Alfred the Great's translation of Orosius uses the name Burgenda land. The poet and early mythologist Victor Rydberg (1828–1895), asserted from an early medieval source Vita Sigismundi, that the Burgundians themselves retained oral traditions about their Scandinavian origin. Their language survived until the seventh century and the feeling of being a Burgundian lasted strongly into the ninth before becoming subsumed into the empire of Charlemagne. Burgundian names for settlements survive today in the suffixes -ingos, -ans and -ens. It continued as the name of a kingdom for a long time, even to the time of Joan of Arc and the 15th century. It also remains the name of a region, formerly a county, in France, variously called Bourgogne (French), Burgundy (English) or Burgund (German). |

|||

|

|||

Early historyThe earliest Roman sources, including Tacitus, make no mention of the original homeland of the Burgundians. After possibly having dwelt in the Vistula basin, according to the mid-6th century historian of the Goths, Jordanes, they were beaten there in battle by Fastida, king of the Gepids and were overwhelmed, almost annihilated. They migrated westwards in the 4th century CE, and settled in the Rhine Valley during the Völkerwanderung, or Germanic migrations. Somewhere in the east they were converted to the Arian form of Christianity, which long sustained a gulf of suspicion and distrust between Burgundians and the Catholic Roman Empire of the West. Divisions were evidently healed or healing circa AD 500, however, as Gundobad, the second to last Burgundian king, maintained a close personal friendship with Avitus, the Catholic bishop of Vienne. Moreover, Gundobad's son and successor, Sigismund, was himself a Catholic, and there is evidence that many of the Burgundian people had converted by this time as well, including several female members of the ruling family. There was, it seems at times a friendly relationship between the Huns and the Burgundians. It was a Hunnish custom for females to have their skull artificially elongated by tight binding of the skull when the child was an infant. Germanic graves are sometimes found with Hunnish ornaments but also with skulls of females that have been treated in this way; west of the Rhine only Burgundian graves contain a large number of such skulls. (Werner, 1953) In the Rhineland, though the Burgundians were nominally Roman foederati, they periodically raided portions of eastern Gaul. Burgundians lived in an uneasy relationship with the imperial Roman government: in 370 the western Emperor Valentinian I attempted to enlist the Burgundians against their enemies the Alamanni, promising to support them with Roman forces. Negotiations with the Burgundians broke down when Valentinian, not understanding that a Germanic treaty was essentially a personal bond, refused to meet with the Burgundian envoys and give them his promise of Roman support.

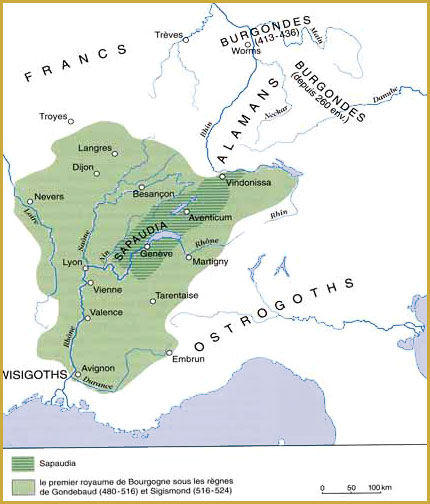

The Burgundian kingdomIn 411, the Burgundian king Gundahar or "Gundicar" set up a puppet emperor, Jovinus, in cooperation with Goar, king of the Alans. With the authority of the Gallic emperor that he controlled, Gundahar settled on the left bank of the Rhine (the Roman side) between the river Lauter and the Nahe. Burgundian raids into Roman Upper Gallia Belgica became intolerable and were ruthlessly brought to an end in 436, when the Roman general Aëtius called in Hun mercenaries who overwhelmed the Rhineland kingdom (with its capital at the old Celtic Roman settlement of Borbetomagus Worms in 437. Gundahar was killed in the fighting, reportedly along with the majority of the Burgundian tribe. The destruction of Worms and the Burgundian kingdom by the Huns became the subject of heroic legends that were afterwards incorporated in the Nibelungenlied, on which Wagner based his Ring Cycle where King Gunther (Gundahar) and Queen Brünhild hold their court at Worms, and Siegfried comes to woo Kriemhild. (In Old Norse sources the names are Gunnar, Brynhild, and Gudrún as normally rendered in English.) In fact, the Atli of the Nibelungenlied is based on Attila the Hun. There is an interesting contemporary account of the conversion of the Burgundians to Christianity told in relation to their conflicts with the Huns. According to the Greek historian Socrates the Scholastic (c.380-450 CE, author of an Ecclesiastical History which describes the events of his time up to about 440 CE, but which goes as far as to falsify historical events at times), the Burgundians were governed by a High Priest, the Sinistus, and by a king elected by the people (who could also be removed from power by the people). When the army suffered defeats, when harvests were poor, when an epidemic struck the tribe, the people would immediately depose the king, holding him personally responsible for not having won the favour of the gods: such was their law. In light of this, an immediate consequence of the destructive raids of the Huns was the removal of the Burgundian king by his subjects. The barbarians, however, went further: they deposed their Sinistus, turning instead to a Christian priest, in this case the bishop (later Saint) Severus of Treves, to obtain the protection of his god, who seemed more powerful then their own. The bishop said to them that the surest way to protect themselves against the invaders was to be baptised: "Stay here", he said to them, "you must fast for seven days, and I will instruct you in the Christian religion and baptise you." The Burgundians complied, and, after the period of fasting, the bishop baptised them, or at least baptised their principal chiefs in the name of the Burgundian people. Believing that they were now under the protection of the most powerful of the gods, the Burgundians subsequently launched an attack on the Huns, with only 3000 warriors against 10,000, and their newfound faith (unless it was just the effects of the Burgundian wine), did the rest. Octar, the chief of the Huns, being drunk in the midst of an orgy, died the night before the Burgundian attack, and his Huns were cut into pieces. This was in the year 430. (Source: Atilla by Roger Caratini). The accepted account of their conversion is somewhat less dramatic. Somewhere in the east the Burgundians had been converted to the Arian form of Christianity, which proved a source of suspicion and distrust between the Burgundians and the Catholic Western Roman Empire. Divisions were evidently healed or healing circa AD 500, however, as Gundobad, one of the last Burgundian kings, maintained a close personal friendship with Avitus, the Catholic bishop of Vienna. Moreover, Gundobad's son and successor, Sigismund, was himself a Catholic, and there is evidence that many of the Burgundian people had converted by this time as well, including several female members of the ruling family. Under the new king Gunderic (died c. 473), the refugees from the destruction were settled by Aëtius near Lugdunensis, known today as Lyon, which was formally the capital of the new Burgundian kingdom by 461. In all, eight Burgundians kings of the house of Gundahar ruled until the kingdom was overrun by the Franks in 534.  As foederati or allies of Rome in its last decades, the Burgundians fought alongside Aetius and a confederation of Visigoths and others in the final defeat of Attila at the Battle of Chalons("Catalaunian Fields") in 451. But Burgundian support couldn't invariably be counted on as the Western empire foundered. An ambiguous reference infidoque tibi Burdundio ductu (Sidonius Apollinaris in Panegyr. Avit. 442.) implicates an unnamed treacherous Burgundian leader in the murder of the emperor Maxentius, which lead directly to the sack of Rome by the Vandals in 455. Perhaps Burgundian concerns lay elsewhere: two Burgundian leaders Chilperic and Gundioc accompanied the Visigothic king Theodoric in his invasion of Spain later that same year, according to Jordanes, Getica (ch.231).  The Burgundians were extending their power over southeastern Gaul; that is, northern Italy, western Switzerland, and southeastern France. In 493 Clovis, king of the Franks, married the Burgundian princess Clotilda, daughter of Chilperic. At first allies with Clovis' Franks against the Visigoths in the early 6th century, the Burgundians were eventually conquered by the Franks in 534 CE. The Burgundian kingdom was made part of the Merovingian kingdoms, and the Burgundians themselves were by and large absorbed as well. The Burgundian LawsOne of the earliest Germanic legal codes, the

Lex Gundobada or Lex Burgundiorum,

is a written collection of laws issued by king Gundobad, (reigned 474 516)

the best-known of the Burgundian kings. The Lex

Gundobada was a record of Burgundian customary law and is typical

of the many Germanic law codes from the period. The Lex

Romana Burgundionum was Gundobad's contribution towards providing

laws for his Roman subjects as well as the Burgundians. Finally, King

Sigismund, who died 523/4 had the Burgundian Prima

Constitutio written down.

Origin of BurgundyThe name of the Burgundians has since remained connected

to the area of modern France that still bears their name: see the later

history of Burgundy. Between the 6th and 20th centuries, however, the

boundaries and political connections of this area have changed frequently;

none of those changes have had anything to do with the original Burgundians.

The name Burgundians used here

and generally used by English writers to refer to the Burgundes is a later

formation and more precisely refers to the inhabitants of the territory

of Burgundy which was named from the people called Burgundes. The descendants

of the Burgundians today are found primarily among the French-speaking

Swiss and neighbouring regions of France.

See alsoFor later legends

of the Burgundian kings, see Nibelung.

For a list of Kings of Burgundy, see

King of Burgundy.

References

External linksSource: Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

© 2001-2005 Wikipedia

contributors (Disclaimer) |

|||

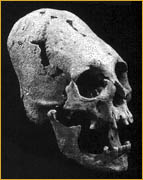

| :: Cranial Deformation Archeologists have identified the first Burgundian cemeteries owing to the presence of individuals with cranial deformations. The majority of these remains were discovered on the banks of the river Leman, notably at Geneva, Nyon, Genolfier, St-Prex, Lausanne and La Tour-de-Peilz. According to barbarian custom, the skulls of children

were subjected to deformation for aesthetic reasons. The majority of the

modified remains were of women. This practice was common amongst the nomadic

tribes of the East, notably the Huns, who were for a time allied with

the Burgundians. "It is tempting, therefore, to suppose that these deformed

skulls belonged to foreign individuals who were associated by marriage

to the Burgundians", says Justin Favrod. We could speculate about the

Alans, a people of Iranian origin who had entered into contact with the

Burgundians in the Rhineland. Nonetheless, the practice of cranial deformation

did not endure. It seems to have dissapeared quite rapidly following the

establishment of the Burgundian monarchy. |

|||